April 2021

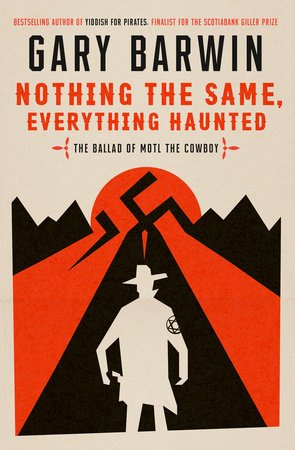

Barwin’s latest book, Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted, explores genocide, persecution, colonialism and masculinity with characteristic irony.

1. Vilnius (Vilna), Lithuania. July 1941

Motl. Jewish cowpoke. Brisket Boy. My grandfather.

As usual, he was bent over the kitchen table, his mottled and hairy nose deep in the pale valley of a book, half-finished plate of herring beside his elbow, half-eaten egg bread slumped beside a Shabbos candlestick. His old mother was out shopping for food while she still could.

So, this Motl, was he a reader?

If the world was ending, he would keep reading.

The world was ending. He was still reading.

So, what was this book he had to read despite everything?

One of the great westerns of the American frontier, of course. Even though he knew that Hitler adored them.

“The master race should be brave as Indianers,” Der Führer had said, and sent boxes of Karl May’s Winnetou noble savage novels to the eastern front to inspire his troops – those same manifest destiny soldiers crossing the country with orders to kill Motl, his mother and all the other Jews.

Did Motl intend to do something about this?

Yes. He would sit at the table, his shlumpy jacket turned up at the collar, his hat like a shroud of mice askew on his sallow head, and read.

Was Motl a man of action?

“If parking his tuches all day and all night on a chair doing nothing but reading is action,” his mother would say, “he’s a man of action. Action, sure. Every day he gets older and more in my way.”

Why was he still reading this western?

Because Motl, this Litvak, this Lithuanian Jew, this inconceivable zaidy, my grandfather, this citizen of the Wild East—that brave old world of ever-present sorrow, a sorrow that had just gotten worse—had chosen the life of the cowboy.

He would be that hombre who sits on his chair and imagines being calm and steady and manly, speaking only the fewest of well-chosen words, doing only what he wanted and what he must under that vast, unpatented western sky.

“And why not?” he would say. “Should my life be nothing but the minced despair and boiled hope of an aging Jew, too thin to be anything but borscht made by Nazis? I choose to think myself a Paleface chuck line rider of the doleful countenance, a Quixotic Ashkenazi of the bronco, riding the Ostland trail. Like my mother said when I told her I wanted to be a doctor, ‘Mazel tov, Motl. Nothing is impossible when it’s an illusion.’”

He would say, “What’s the difference between a Jewish cowpoke and beef jerky? It’s the hat. And feeling empty as a broken barrel. Jerky don’t never feel such hollowness, least not by the time it’s jerky. But the cowboy, the cowboy keeps riding. He don’t look back. Eventually, if he’s lucky, he too becomes leathernand feels only what jerky feels.”

Motl. Citizen of Vilna. Saddlebag of pain. Feedbag of Regret.

At forty-five, he had a history. As a Lithuanian Jew, he was pickled in it.

But though neither he nor his mother knew it at the time, something had changed. Somewhere, deep down in the overworked mine shaft of his imagination, it had been determined that he would set out on a perilous adventure, this time of his own choosing. He would get up on his horse and ride.

And he would have a child.

At his age.

And avoid being killed. Sometimes you have to save your own bacon, when you’re a Jew.

The next day, he went to the barber’s. Even a grown man will cave in to his mother’s demands that he groom if she won’t make food for him. Eyes closed, a Texas reverie floating through his mind like the scent of campfire, Motl lay back in the red chair and awaited his shave.

But then:

“Under a hot towel, a cowpoke can think big thoughts, but to act he must stand up,” he said.

He stood up.

For a moment, the towel hung from his jowls, the Santa beard of a Hebrew god. Then it fell away.

“Barber,” Motl said. “I must seize these last days while the possibility of life remains.”

The barber said nothing, wet blade held between trembling fingers.

“The kabbalists speak of repairing the world, healing what is broken. It’s my time,” he said, looking round that hair-strewn palace of strop and whisker, that little shop of Hebrews.

“Barber, I thank you, for I have learned much under your towel.” Shave and a haircut.

Did the barber, Shmuel, expect payment? Two bits.

Did Motl toss him these two coins before his impromptu departure?

Having had neither shave nor haircut, he only waved, then hightailed it into the bright sun of Shnipishok, that region of Vilna whose name sounds like scissor blades. He ran through its streets, feeling open to possibility and getaway.

Did Shmuel chase him with his blade?

Let’s say it was a close shave.

Copyright © 2021 Gary Barwin. Published by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.