September, 2015

by Ramona Matthews

I want to take you back to March 1965. When we turned the dial on our living room TVs to CHCH or CBC, coverage of American issues often topped the news, from the Vietnam war to the civil rights actions in Selma, Alabama. And what had been going on in Selma since the new year began? Voting rights were being denied to 98 per cent of the black citizens there and Martin Luther King Jr. and his associates had mobilized supporters to try, in a non-violent way, to change that.

Dr. King had galvanized the world with his “I Have a Dream” speech almost two years earlier, and his efforts had already earned him the Nobel Prize for Peace just months before. That this was hard slogging is an understatement. In his speeches Martin Luther King Jr. would compare the aims of the movement he represented with the Exodus that is so familiar to you. Singers aligned with them would motivate people with familiar songs such as “We Shall Overcome” and that wonderful African-American spiritual “Let My People Go.”

Meanwhile, here in Hamilton, my father-in-law, the late Reverend Alan Matthews, arrived home on Saturday night, March 13, after a long drive alone from Kingston. The house in which the Matthews family lived — on Wood Street in the north end — was attached to the church at which Alan was the pastor, Eastwood Baptist. Alan, his wife Jean, and three young sons, Bruce, Ron and John, lived there and their married daughter and her young family were nearby.

Alan had just spent four days visiting convicts in Kingston Penitentiary — people he knew and had worked with from this area who were incarcerated in the federal system and serving long jail sentences. Jean asked Alan to return a call made by Eugene Weiner when he got in the door; no, she didn’t know why he had called.

It was not unusual for people to call and ask for Reverend Al’s help or opinion. But this call was different. Help was not being sought from the other end; an offer was being made. And, as Alan put it in his writings,

“The next day we were on the plane at Malton International Airport to march with Martin Luther King ...

“A week after (the event known as) Bloody Sunday I arrived at Selma ... to join (a large group of) marchers to proclaim what we felt was justice – a spiritual concern to all.”

Some 200 Alabama State troopers had clashed with 525 civil rights demonstrators on Bloody Sunday, clubbing and tear-gassing them. Things were getting uglier in Selma.

Maybe you know about the situation at that time in Alabama. Martin Luther King Jr. had asked religious leaders of all denominations and faiths to come to the city of Selma and join the massive undertaking to ensure equal voting rights for both white and black citizens. Martin Luther King Jr. was all about knocking on God’s door and inviting others to help him to do the same.

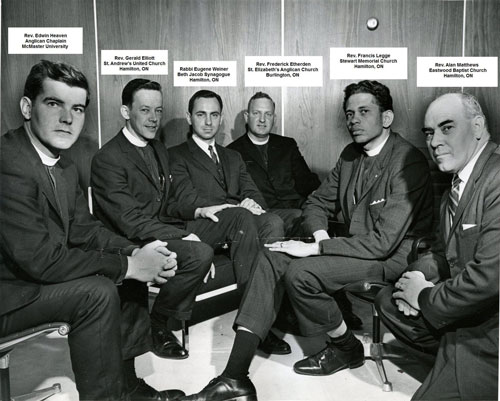

Your young rabbi from this synagogue in what was a small industrial city in Canada apparently answered the call at the urging of a friend. And — remarkably — he didn’t choose to go it alone. Funds were provided by someone or maybe a few people from your congregation to sponsor four other clergymen to join him too — and they were all Christian. In addition to Alan, there were two Anglican priests and a United Church minister sponsored by Beth Jacob — Rev. Edwin Heaven, Anglican chaplain of McMaster University; Rev. Frederick Etherden of St. Elizabeth’s Anglican Church in Burlington; and Rev. Gerald Elliott of St. Andrew’s United Church, previously minister of a congregation on the Six Nations Reserve. Two Unitarian ministers also joined them, as well the young pastor from Stewart Memorial Church here in the city. Interestingly, that congregation was formed in 1835 by both black free men and slaves who escaped bondage and settled here.

They were gone only a few days — from Sunday to Wednesday — but what a time it was.

Among Alan’s writings was this description: “Priests and ministers formed the outside lines. Nuns were in the third line and Blacks were further back. We would line up and push forward, sometimes as little as one or two feet. Joan Baez led in much of the singing of 'We Shall Overcome' and other similar songs of freedom and right. Because of this (which was a) walk to City Hall, many Black people were registered as voters. Many were too timid to register for a long time."

I’d like to read you a few more excerpts from Alan’s writing:

“Martin Luther King gave a stringent orientation which included, 'You are here to witness, not be abusive or to fight. Do not run away from the scene. You will feel and see hate — show love. If physically attacked, fall face down and cover your heads. DO NOT retaliate. Peace, love will win.'

“Between gas fumes, not much food, anger, confusion, anxiety, boredom from just waiting, with little movement, many fainted and felt sick.

“We slept on straw mattresses on the floor of the Roman Catholic Good Shepherd Hospital. There was only 10 inches between mattresses.

“I never saw such hatred.”

As for your own rabbi, on the second day there, Eugene Weiner was asked to give the benediction at a memorial service commemorating the life of a Unitarian minister, the Rev. James Reeb. He had been murdered by fellow white men the previous week.

In his book The Selma Awakening by Mark D. Morrison-Reed, there is a beautiful anecdote about this service. “Following King, Dana McLean Greeley offered a prayer that ended with the Lord’s Prayer. Then everyone rose and sang “We Shall Overcome.”

Christopher Raible remembered, “When we had sung four stanzas, we hummed, and a rabbi (Eugene Weiner), who had been asked to give the benediction, stepped to the pulpit. He repeated in Hebrew the great Kaddish, the memorial prayer for the dead, over our humming. As he completed it, we sang again, and from nowhere there came two little Negro girls who began to sing a high piercing descant above our singing. The rabbi leaned down, picked up the four-year-old, and held her in his arms. And the tears flowed down my face.” And all around him, people were crying.

On arrival back in Hamilton, the group of six — Rabbi Weiner, the four he had recruited and Rev. Francis Legge of Stewart Memorial — found themselves the objects of great interest. A special reception was held by Mayor Vic Copps the day after they got home, and the following weekend a meeting was held for the general public at Zion United Church downtown. We know that Alan and Gerald Elliott were asked to speak about their experiences from time to time as the years went on and imagine the others did too.

A Globe and Mail article is perhaps the most telling for us in 2015. When interviewed right after they arrived back both Rabbi Weiner and Rev. Etherden drew parallels with the situation then here in Canada. Rev. Etherden said, “I think we ought to make statements, present briefs and eventually protest to the nation’s capital in a dramatic way if need be that many of our Canadians are not created equal.” He cited both the French-English situation and the plight of aboriginal people.

Rabbi Weiner was quoted as saying, “I personally feel that the church and the synagogue have been very remiss in their response to deal with the outstanding social issues. I agree with Dr. King that (the faith community) tends to be an echo rather than a voice and a taillight rather than a headlight.”

Alan Matthews went on to leave Eastwood Church and took his ministry in a new direction, establishing the Hamilton organization that was known as Alienated Youth or AY. Interestingly, none of Alan’s sons recall him ever speaking of going to Selma, just as he seldom spoke of his time in service during the Second World War. His son John describes Alan as a “here and now” person.

“The ‘here and now’ of disadvantaged and troubled young people was front and centre in his life ... almost an obsession,” relates John.

“Generally it was simply a fact in our home that Martin Luther King Jr. had a very powerful impact on dad.”

Alan never sought recognition for himself and was very honoured to be selected as Hamilton’s Man of the Year in 1978, just as he was surprised to be selected for the conferring of an honorary Doctorate of Divinity from McGill before he retired. Alan certainly lived by the motto that was the title of his book — Together We Can. He died 26 years ago at age 71.

Rabbi Eugene Weiner didn’t stay in Hamilton long but went on to do illustrious things in Israel. I was so impressed to read his obituary from the Haaretz newspaper. A man of conviction, he was one who coached others through their tough wildernesses of life and sought and taught understanding. He certainly maximized his “three score years and ten” before he died in 2003.

There are Selmas in our day and age, and in truth we’re probably aware of them, large movements to which we can choose to commit our time and efforts — so many of them, with so many people in our world bound in oppression and injustice. But there are little Selmas, too, perhaps in our neighbourhoods, our schools, our places of work. It’s something we all might consider as we leave this place today.

Ramona Matthews taught for three decades in the Toronto District School Board. Her love for family stories has led her to carry out extensive research into both her husband’s family history, as well as her own family’s Ukrainian-Canadian roots.

Watch: Ramona and Ron Matthews share the Reverend Matthews's recollections about Selma

0Comments

Add CommentPlease login to leave a comment